Sudarshawn Damodharan, DO; Eric Monroe, MD

WMJ. 2024;123(2):76-77

Retinoblastoma is the most common intraocular malignancy in children, with an estimated 300 new cases in the United States each year.1,2 Its cause is related to germline or sporadic mutations of the RB1 gene – a tumor suppressor gene,3 and it can form in one or both eyes. It typically presents early in childhood, with the majority of patients presenting before 5 years of age, and the median age of diagnoses is just shy of 2 years. It should considered for any child who presents with leukocoria or strabismus, and the patient should be referred to an ophthalmologist for further evaluation.

The earlier a patient is diagnosed with retinoblastoma, the better the outcome from a vision and survival perspective. Treatment for retinoblastoma has evolved over time, from surgical removal of the affected eye, to local radiation and cryo and laser therapies, along with systemic chemotherapy.3 Unfortunately, many side effects were seen from conventional, systemic retinoblastoma therapy, which led to the emergence of intra-arterial chemotherapy (IAC) as a treatment option. Retinoblastoma contains itself to the eye in its early stages, which makes it amenable to localized therapy with fewer side effects compared to systemic therapy. Ongoing research studies have demonstrated that IAC for retinoblastoma is efficacious, with improved quality of life and overall survival.

IAC and retinoblastoma treatment involves a multidisciplinary team that includes ophthalmologists, oncologists, and interventional radiologists. The procedure involves putting the child under anesthesia, then introducing a small catheter into the femoral artery. This catheter is then navigated until the ophthalmic artery is reached. Once this occurs, the chemotherapy can be delivered directly to the tumor area. Since the concentration of the chemotherapy given locally is higher, the amount is significantly decreased (~5%) to what would have been given systemically.4 This treatment is repeated about monthly for at least 3 courses, with interval eye examinations performed in between for further assessment and local therapy (ie, cryo and laser therapies) provided by ophthalmologists as needed. Because of the intricacy of the IAC procedure, it is only offered at a select number of institutions that have an experienced team capable of providing this therapy.

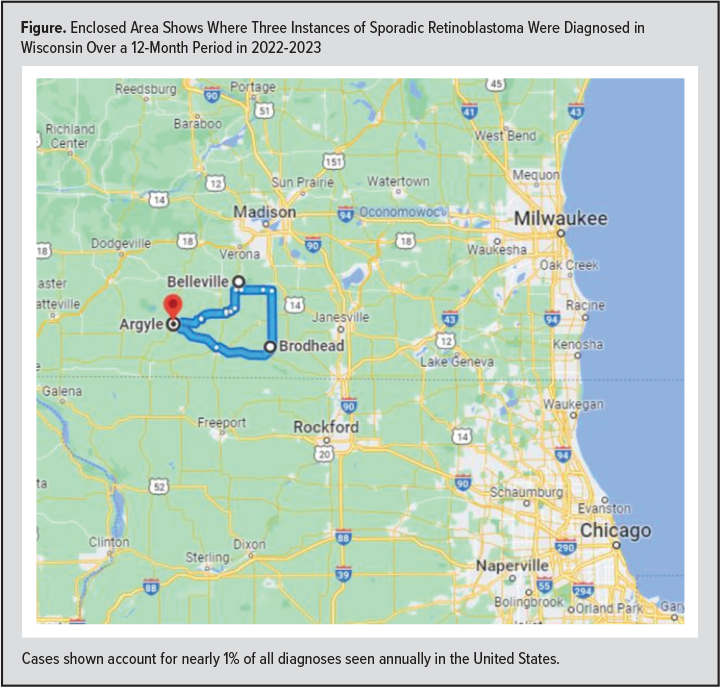

Since starting the IAC program at the University of Wisconsin American Family Children’s Hospital in 2022, 4 new patients have presented with retinoblastoma: one with a germline and three with sporadic mutations of the RB1 gene. When looking closer at the geographical location of these patients, it was noticed that the three sporadic retinoblastoma patients all lived within close proximity to one another (Figure). Given the rarity of this disease and with nearly 1% of all instances of retinoblastoma found in such a small area, it raises the question of a possible environmental cause that should be explored.

Since starting the IAC program at the University of Wisconsin American Family Children’s Hospital in 2022, 4 new patients have presented with retinoblastoma: one with a germline and three with sporadic mutations of the RB1 gene. When looking closer at the geographical location of these patients, it was noticed that the three sporadic retinoblastoma patients all lived within close proximity to one another (Figure). Given the rarity of this disease and with nearly 1% of all instances of retinoblastoma found in such a small area, it raises the question of a possible environmental cause that should be explored.

The genetic basis for the development of retinoblastoma has been well described, but it may be possible that an environmental stimulus could play a role in causing an alteration in the RB1 gene responsible for tumor development. When scouring the literature, there does not seem to be any known environmental cause that related to the development of retinoblastoma in children. However, toxins and other environmental stimuli have been linked to the development of different types of cancers more commonly seen in adults, which does make the basis of this possible. With such a high proportion of sporadic retinoblastoma diagnosis in a short period and seen in a small geographical area within Wisconsin, further investigation is warranted prior to determining coincidental causation for the health of the patients we care for.

REFERENCES

- Aerts I, Lumbroso-Le Rouic L, Gauthier-Villars M, Brisse H, Doz F, Desjardins L. Retinoblastoma. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2006;1:31. doi:0.1186/1750-1172-1-31

- Kadom N, Sze RW. Radiological reasoning: leukocoria in a child. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;191(3 Suppl):S40–44. doi:10.2214/AJR.07.7022

- Dimaras H, Corson TW, Cobrinik D, et al. Retinoblastoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2015;1:15021. doi:10.1038/nrdp.2015.21

- Shields CL, Manjandavida FP, Lally SE, et al. Intra-arterial chemotherapy for retinoblastoma in 70 eyes: outcomes based on the international classification of retinoblastoma. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(7):1453-1460. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.01.026