Ankit Choudhury, BA; Sagar S. Matharu, BS

WMJ. 2025;124(5):410-411.

We are both Indian American medical students with culturally distinct names – Ankit and Sagar. Through our experiences, we hope to spotlight the profound impact one’s name has in shaping perceptions in medicine.

Ankit grew up in the Midwest, and his name was rarely pronounced as his parents intended. To ease interactions, he introduced himself as “Ann-kit,” instead of the correct, “Ahn-kith.” This alteration minimized discomfort–both his and others’. However, when he entered college and was exposed to a more diverse and culturally aware community, he gained the confidence to embrace a pronunciation closer to its true form: “Ahn-kit.” It’s a little closer, but not quite correct, and he was still hesitant to share the authentic pronunciation of his name except with those who shared his cultural heritage.

Similar to Ankit, Sagar tends to introduce himself this way: “Sagar, but it’s like Soccer with a G.” While it may be tongue-in-cheek, it serves as a preemptive strike against inevitable mispronunciations, as in this example:

“Where are you from, ‘Cigar’? the patient asks, head tilted in curiosity.

“Maryland,” responds Sagar with a practiced smile.

“Oh.” The patient hesitates, slightly nodding his head, “Where are you really from?”

A bit taken aback – even though he has heard this before – Sagar replies, “Oh right, my family is from India,” trying to maintain a stiffened smile.

Moments like these are not new for us. Our names, unfamiliar to many, often function as a signal, prompting assumptions about our background before we have the chance to define ourselves. Names carry immense significance: they are the quintessential marker of who you are. For us, introducing ourselves has always been a lifelong balancing act. These subtle, yet impactful, moments of identity negotiation have shaped our interpersonal dynamics and professional experiences, highlighting how deeply ingrained perceptions influence interactions in medicine.

In medical school, we often find ourselves weighing the desire for proper pronunciation of our names against the fear of bringing too much attention to ourselves. Introducing ourselves in clinical or academic settings involves an unspoken calculation: is it worth the time and discomfort to ensure a proper pronunciation of our names? Or does correcting someone detract from the task at hand?

Names can also serve as bridges, connecting us to others in profound ways. Before medical school, Ankit worked as a medical assistant at a gastroenterology clinic in Missouri. One patient, noticing his nametag, asked, “Are you Indian?” Their shared heritage led to a warm conversation about a familiar cultural experience. Such moments of bonding, while brief, bridge a gap of understanding that allows the patient to feel seen and heard in a way that extends beyond the standard provider-patient relationship.

Ankit previously worked with a physician who was an immigrant from India and who often tailored care to reflect cultural nuances. For instance, he encouraged providing modified colonoscopy prep instructions to include dietary swaps familiar to Indian cultures, ensuring adherence without disrupting cultural norms. This is a poignant reminder that diversity in medicine enriches care by fostering authentic empathy alongside cultural competency.

Diversity is a systemic necessity, enriching health care by reflecting the communities it serves. When patients see their identities mirrored in their providers, it fosters trust and improves care.1-3 Embracing our identities as Indian Americans has become a source of strength, informing our interactions with patients.

Diversity in medical education is not just an abstract ideal; it is a practical necessity. A diverse learning environment enriches the educational experience, equipping future physicians to provide culturally sensitive care. Yet, the system often overlooks the nuances of identity. While medical education celebrates diversity on paper, it rarely addresses the practical challenges that come with it. How do we foster inclusivity when names are mispronounced, cultural differences are misunderstood, or identities are reduced to stereotypes?

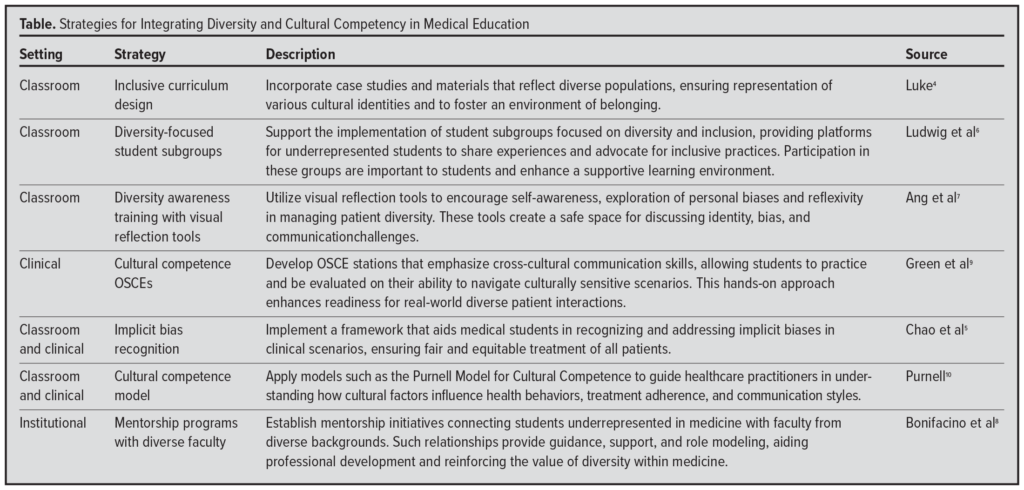

Fostering inclusivity in medicine starts with integrating diverse realities into medical curriculum. Case studies reflecting cultural nuances and open dialogues about identities, bias, and health beliefs cultivate understanding and cultural humility.4 Workshops on implicit bias and structured discussions about identity in clinical practice equip future physicians with empathy and sensitivity.5-7

Beyond the classroom, medical institutions can support mentorship programs that connect underrepresented students with role models who share their backgrounds.8 Representation matters not only for the aspiring physician, but also for the patients we serve. A diverse physician workforce allows the diverse patient population to feel seen, understood, and represented during their most vulnerable moments. (The Table provides an overview of several evidence-based strategies.)

Beyond the classroom, medical institutions can support mentorship programs that connect underrepresented students with role models who share their backgrounds.8 Representation matters not only for the aspiring physician, but also for the patients we serve. A diverse physician workforce allows the diverse patient population to feel seen, understood, and represented during their most vulnerable moments. (The Table provides an overview of several evidence-based strategies.)

Identity in medicine weaves into a larger tapestry, bridging gaps in understanding and building trust with communities. This trust is vital in addressing health disparities, fostering patient compliance, and ensuring equitable care. The richness of diversity is a strength, not just for individuals navigating the complexities of medical education but for the entire health care system striving to deliver compassionate and culturally sensitive care.

The patient’s question, “Where are you really from?” isn’t just about our origin; it is a reminder of how names often carry more than just phonetic weight. Reclaiming our names has been an act of reclaiming our identities, a refusal to let them be diminished or overlooked.

Names are more than identifiers. They are a bridge to understanding, offering opportunities to connect with others in ways that transcend language. In medicine, where connection and trust are paramount, acknowledging the importance of a name is not just politeness – it enhances the quality of care. When institutions create spaces where every name is valued, they send a powerful message: every identity matters.

REFERENCES

- Saha S, Komaromy M, Koepsell TD, Bindman AB. Patient-physician racial concordance and the perceived quality and use of health care. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(9):997-1004. doi:10.1001/archinte.159.9.997

- Nazione S, Perrault EK, Keating DM. Finding common ground: can provider-patient race concordance and self-disclosure bolster patient trust, perceptions, and intentions?. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2019;6(5):962-972. doi:10.1007/s40615-019-00597-6

- Moore C, Coates E, Watson A, de Heer R, McLeod A, Prudhomme A. “It’s important to work with people that look like me”: Black patients’ preferences for patient-provider race concordance. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2023;10(5):2552-2564. doi:10.1007/s40615-022-01435-y

- Luke K. Twelve tips for designing an inclusive curriculum in medical education using Universal Design for Learning (UDL) principles. MedEdPublish (2016). 2021;10:118. doi:10.15694/mep.2021.000118.1

- Chao ICI, Violato E, Concannon B, McCartan C, King S, Roberts MR. Ethnic and gender bias in Objective Structured Clinical Examination: a critical review. Educ Health Prof. 2021;4(2):37-49. doi:10.4103/EHP.EHP_2_21

- Ludwig S, Dettmer S, Wurl W, Seeland U, Maaz A, Peters H. Evaluation of curricular relevance and actual integration of sex/gender and cultural competencies by final year medical students: effects of student diversity subgroups and curriculum. GMS J Med Educ. 2020;37(2):Doc19. doi:10.3205/zma001312

- Ang W, Verpooten L, De Winter B, Bombeke K. Diversity awareness in medical education: an innovative training with visual reflection tools. Perspect Med Educ. 2023;12(1):480-487. doi:10.5334/pme.1080

- Bonifacino E, Ufomata EO, Farkas AH, Turner R, Corbelli JA. Mentorship of underrepresented physicians and trainees in academic medicine: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(4):1023-1034. doi:10.1007/s11606-020-06478-7

- Green AR, Miller E, Krupat E, et al. Designing and implementing a cultural competence OSCE: lessons learned from interviews with medical students. Ethn Dis. 2007;17(2):344-350.

- Purnell L. The Purnell Model for Cultural Competence. J Transcult Nurs. 2002;13(3):193-201. doi:10.1177/10459602013003006